World Purple Day on March 26th is an international effort dedicated to increasing awareness about epilepsy. In commemoration of the day, two TD colleagues spoke about their experiences and what they've learned living with or raising someone living with epilepsy.

Both colleagues agree that it's a topic and condition that warrants more education and awareness for, especially for children.

Each story is unique, yet contain so many similarities in facing the unknown, speaking up for others and much more.

Here are their stories in their own words:

Erin Husenaj, Head of Employee Engagement, TD Bank AMCB

It was April 2018. I was sitting in an exam room, nervously waiting to learn if my seven-year-old daughter, Lilly, had developed a facial tic, or something more. I tried to read the neurologist's expression as she reviewed the EEG report. My husband sat to my right with Lilly in his lap. The ticking of the wall clock was deafening, and the room felt cold and uninviting. I snapped to attention when the neurologist looked up from her notes. The four words that came out of her mouth shattered me "your daughter has epilepsy."

My stomach dropped to the floor and I couldn't feel my legs. How was this possible? What did this mean? My words were stuck somewhere in the bottom of my tightened throat and tears streamed down my face. The doctor continued talking but I couldn't hear anything. I had descended into a rabbit hole of "what ifs".

Four years later, our family has learned, adjusted, and pivoted so much to make sure Lilly is living the most normal, happy life she can, but with epilepsy, you're always on a journey.

We live our lives through alarms every day at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m., when she has to take her medicine.

In the beginning, the darkest days for us, the seizures would come on without warning and every time the school nurse called, my heart stopped. They have to report everything, even a skinned knee, so now when they call the first thing the nurse says is, "everything's fine."

And for the most part, everything is fine. Lilly is one of the lucky ones. She has gained seizure control and we are grateful that she's been able to get to a place that others unfortunately can't.

Her doctor also encourages Lilly to try and live as normal a life as possible. What amazes me the most in the last four years is not only her bravery through this process, but her openness to share.

My first thought when she was diagnosed was, "I don't want anyone to treat her differently." Early on, she had two seizures at school. It touched my heart to see how, kids have embraced and supported her through this. They all made her cards when she was in the hospital and have rallied around her throughout. Lilly also joined the Epilepsy Foundation Kids Crew which has helped her learn from and be with kids going through a similar journey. This also helps her put things into perspective because she sees other children who don't have the same quality of life she has.

It's brought our family closer together than ever and made us more empathetic people as well.

Patience, Persistence and Taking Control

Lilly has really gotten a grasp on her epilepsy through medication and various doctors, but that wasn't always the case.

She didn't have much success at first and we held onto the hope that this would stop over time. But things took a terrifying turn in October 2018. I was upstairs in my bedroom and Lilly's sister ran in shouting "MOM!!!" … "Mom! Lilly fell and hit her head and now there's something wrong with her."

My body reacted the same way it did that day in the neurologist's office. Panic propelled me down the stairs two at a time, but I couldn't find her. "Where is she?!?" I screamed. Then I looked to my right. There was Lilly, on the floor in between the couch and the coffee table. She was violently convulsing, and her skin was a shade of bluish gray. It was the worst kind of seizure. We launched into a series of firsts that night. The first time calling 911. The first-time riding in an ambulance. The first time rushing into a pediatric ER. The first time I thought I could lose my daughter... Over the next few months, Lilly would go on to have several more seizures like this and what we experienced during that time would change my outlook on life completely.

For months, I felt like I was walking around in a fog. You just can't turn your mind off.

We eventually had to learn things like how it was okay to ask for other opinions and try new treatments. We had to take control of Lilly's health journey.

Don't be afraid to make changes when things don't feel right . It's something I wish we had done sooner. You empowered to do that. We didn't know things could be better somewhere else. And in fact, that's changed everything for us.

Ask for and Receive Help

Another thing we learned as a family during this journey was how much people want to and can help you.

Lilly had an army of people running toward her to make sure she was okay. Kids, parents, family, friends – no one ran away, and their support contributed to her resilience.

I remember being with one of Lilly's teachers and telling her that she wasn't coming to class because she had suffered a seizure the night before.

She looked at me and said, "How are you doing?"

I just burst out crying because no one had asked me that to that point. She gave me a hug and I didn't realize until that moment, how much I needed that and how much a little kindness can help someone.

People are always willing to help, they may not know how or if you need help if you aren't open to it.

Lilly's friends and their parents have embraced her. She still lives a very full life and we haven't had to take anything away from her because of her epilepsy.

Talk About It with Others

I was reluctant to talk about it in the beginning, but I talk about it a lot now.

Not only to remove the stigma, but to educate others on how to handle this and what to do if someone has a seizure in front of you.

That's the only way people will understand.

Epilepsy can be hard to explain in a way that doesn't sound scary. 1 in 26 people will develop epilepsy at some point in their lifetime. This was a statistic I never knew and one that was somewhat comforting. The more we talked about Lilly, the more it seemed that everyone knew someone who had experience with epilepsy.

Being part of this community has also raised my emotional quotient to a whole new level and has shaped the way I approach all things in life. Most importantly, it's reminded me that nobody has everything, but everybody has something. Together, we celebrate milestones and encourage each other to create positive change.

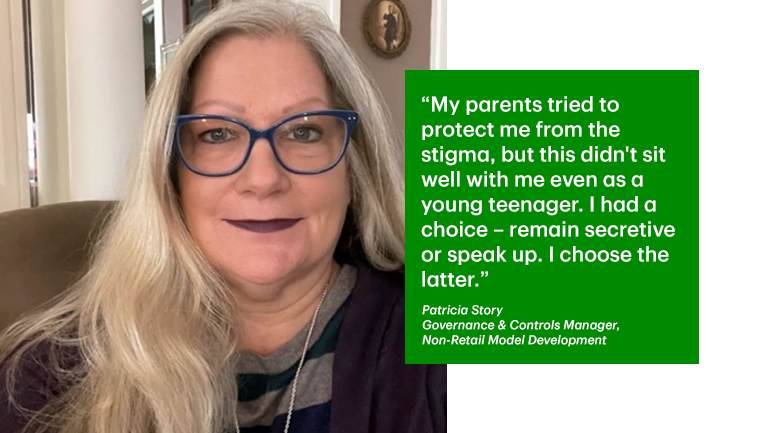

Patricia Story, Governance & Controls Manager, Non-Retail Model Development, TD Bank AMCB

It was 1971 when I had my first seizure. I was 4 years old and sitting at the dinner table with my three older sisters and my parents when suddenly I just slid under the table. It was a grand mal seizure, and it was terrifying. During a seizure my brain was inundated with thousands of images, thoughts, memories, hallucinations– all in a matter of less than a minute. I would have this intense rush in my brain and the ending was always the same. I would awake clearheaded but mentally and physically exhausted to the worried faces of my parents, sisters, and anyone else who had the unfortunate experience of witnessing my seizure. These memories are painful because as a child I didn't know what I was doing to cause all this sadness in the people I loved.

After several hospitalizations and tests, I was finally diagnosed in 1973. I was told I had a 'seizure disorder' and medication would probably manage it. My neurologist had recently lost a pediatric epilepsy patient due to a boating accident, so my parents were given a detailed list of all the things I was not allowed to do growing up in New Hampshire. I couldn't go swimming, ride a bike, ride on a boat, go on a carnival ride – and my parents and sisters protected me vehemently. My seizures were pretty well managed with medication, although there were many adjustments to my medications as I grew up.

I had a classmate who had epilepsy. They were on medication that caused visible impairments, and other classmates would cruelly mock them. When I was in Junior High School, I asked my parents what was different between what I had (known only to me as a 'seizure disorder') and what my classmate had. My mother finally looked at me and said, "there is no difference – you have epilepsy". It was clearly a word that my parents didn't want to use, and it made me feel like I had something shameful and secret. My parents tried to protect me from the stigma, but this didn't sit well with me even as a young teenager. I had a choice – remain secretive or speak up. I choose the latter.

Armed with this new knowledge, I decided to educate the people who were so cruel to my classmate. When I heard the mocking and ignorant comments, I spoke up.

I have been very lucky in that I was able to get off from the medication early in adulthood and I have been able to do all the things I never got to as a child.

Still, this is my advice help anyone supporting someone or living with epilepsy themselves, particularly a child:

- Epilepsy is like operating any electrical device without surge protection. This explanation is the easiest way that I have found to quickly explain what epilepsy is to someone who doesn't know.

- Epilepsy does not impact your intelligence or make you any less capable of achieving your dreams.

- When someone is having a seizure, they do not swallow their tongue and it is not wise to try to hold someone's tongue. All that is needed if you are present while someone is having a seizure is to provide some protection around them, so they don't fall or otherwise hurt themselves on their surroundings.

- The best thing that someone can do to support someone having a seizure is to remain calm and supportive for when the person 'wakes up'. Yelling in someone's face won't 'wake them up' – it will be scary and makes the experience more stressful and difficult when they come out of the seizure and have to address the feelings of the other people in the room.

- A child with epilepsy can do whatever they put their mind to. I believed in my youth that I could not become a mother, that certain careers were not available to me, that I was 'fragile'. Things can be done to protect your child's safety while still allowing them to be children.

- You won't be able to stop the cruelty and ignorance of others completely, but you can help your child by being open about it and discussing the things they hear that are hurtful or ignorant.

- Expose your child to people who have succeeded and show them that anything is possible.