Where does the largest part of your monthly spending go? If you’re like most of the U.S. population, chances are housing is your biggest expense. Though that remains true from coast to coast, the cost of housing can vary a lot from location to location. Why does this happen, and what contributes to this phenomenon? According to a new report from Andrew Foran, Economist for TD Economics, population trends like immigration, birth rates, and labor-force changes all play a big part in how much you pay to live where you do.

Southbound Migration Impacts Offset by International Immigration

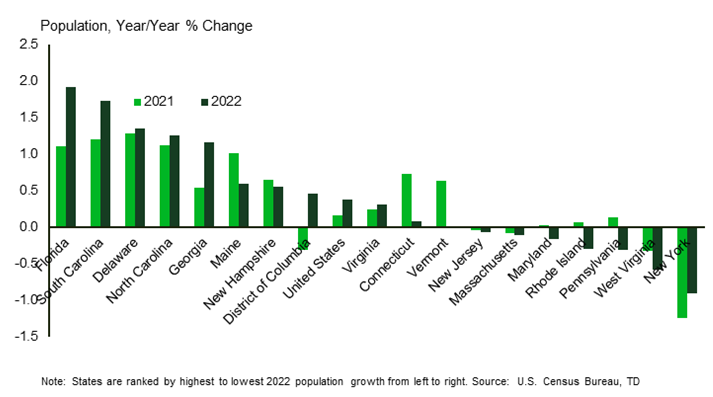

Unsurprisingly, 2020’s pandemic set off an uptick in domestic migration throughout the U.S. population. When teleworking, especially from home, became mandatory for non-essential employees, it inspired many to move to lower-cost regions, especially the South, as shown in Figure 1.

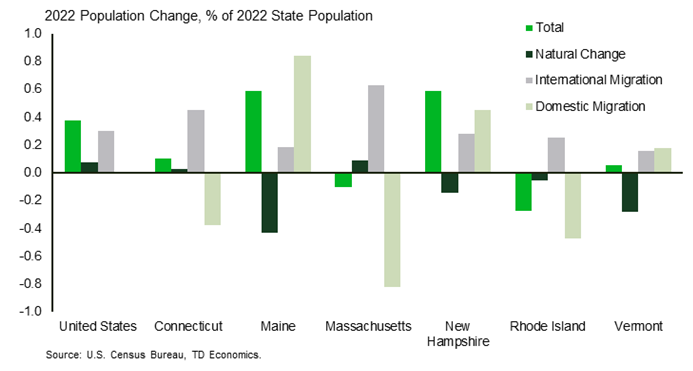

Andrew notes that international immigration into the Northeast states helped to partially offset their population declines resulting from domestic migration outflows, as Figure 2 illustrates.

The migration to the South put strong upward pressure on housing prices in many destination areas. In contrast, housing prices rose by less in most of the Northeast, with states that saw large domestic outflows (such as New York) seeing much more muted price growth.

The pandemic also increased retirement rates, with people close to retirement age opting to leave the workforce sooner than they may have otherwise. This group, in particular, as well as the working population (age 25-54) in general, drove a trend of relocating to southern states like Florida and Texas, both without a state income tax.

While Andrew says it’s difficult to say for sure if this regional immigration trend resulted solely from more employees working from home, it has had labor impacts as the pandemic subsided and people began returning to offices or made hybrid working arrangements with their employers.

“These domestic migration inflows in the South have helped their labor forces recover more quickly from the pandemic, providing the manpower needed to get back to work,” says Andrew. “There still may be issues regarding matching workers with the skills needed for specialized jobs, but in the South, it’s less of a struggle than they’re seeing up north.”

Andrew adds that in some destination states, population growth exceeded employment growth, so it pushed up unemployment rates in those states.

Negative Population Growth

One interesting trend Andrew sees is that Americans are increasingly waiting until their thirties and beyond to have children. Rising childcare and housing costs certainly play a part in that trend.

With birth rates across the country declining since 2010, the U.S. population is seeing slower natural population growth, defined as births minus deaths. Recently we’ve seen a slight recovery in the birth rate, particularly in New Hampshire, which in 2022 saw the strongest growth in births across the U.S. Though they did see that birth increase, New Hampshire still experienced negative “natural” growth across the state in 2022.

Connecticut and Massachusetts both recorded positive natural population increases in 2022, enjoying strong growth in births and a solid decline in deaths relative to 2021. But here again, the birth rate in each state is not where it needs to be to see sustained positive natural growth over the long term. While this trend is more apparent in some of the Northeastern states which have older populations, the trend persists nationally.

Aging Labor Market

As Andrew observes in his report, the slowing natural population growth in the U.S. means that without immigrant workers, the labor force (the number of working-age people who are either employed or actively looking for a job) would face serious challenges.

“Interestingly,” he says, “international migration inflows in the post-pandemic period, mostly occurring in 2022, have been comparatively higher in states that had seen net domestic migration outflows. But in most cases, they were not enough to fully counter those outflows, except in Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Virginia.”

Andrew notes that the Baby Boomer generation is reaching retirement age in huge numbers, and according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), is expected to increase the 65-plus demographic by 1.2 percent each year. “Compare that to the working-age population, aged 25-54, which is only expected to grow by 0.2 percent each year, and it’s easy to see how a widening disparity can have broad economic effects,” he says.

Specific to certain regions like the South, where there has been an increase in interstate migration, Andrew has found better labor supply recovery as the workforce strengthens with more residents in the 25-54 age group. Strong labor force recoveries were highly correlated with housing price increases, as new residents added to the already strong demand for housing brought on by low mortgage rates in the early days of the pandemic.

Moving Forward

In coming years, Andrew cites the aging U.S. population as a key trend to watch, with the international immigration trend complementing that. “Immigration is forecasted to make up a larger share of population growth than it did in pre-pandemic years,” he says. “What’s more, if the birth rate remains as low as it now is, the CBO forecasts that all population growth will be due to international immigration by 2042.”